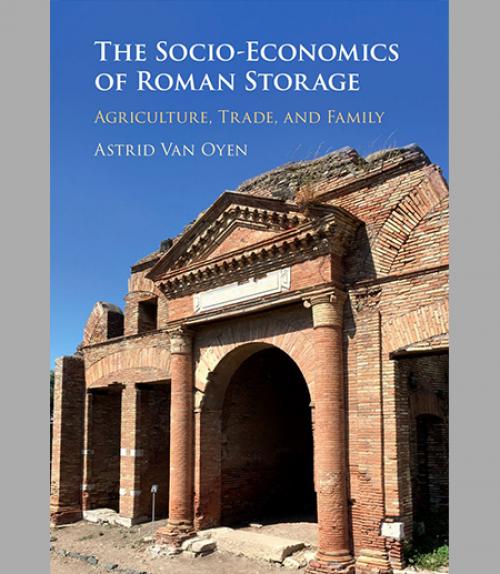

‘Households in Context’ wins Wiseman Book Award

A&S Communications

Department Homepage

The College of Arts & Sciences

Department Homepage

The College of Arts & Sciences